Reading time for children: 6 min

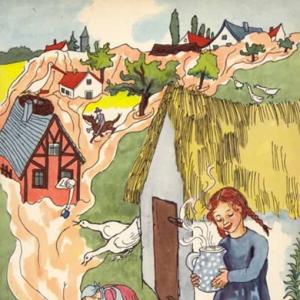

Very often, after a violent thunder-storm, a field of buckwheat appears blackened and singed, as if a flame of fir had passed over it. The country people say that this appearance is caused by lightning; but I will tell you what th sparrow says, and the sparrow heard it from an old willow-tree which grew near a field of buckwheat, and is ther still. It is a large venerable tree, though a little crippled by age. The trunk has been split, and out of the crevic grass and brambles grow. The tree bends for-ward slightly, and the branches hang quite down to the ground jus like green hair

Corn grows in the surrounding fields, not only rye and barley, but oats,– pretty oats that, when ripe, look like a number of little golden canary-birds sitting on a bough. The corn has a smiling look and the heaviest and richest ears bend their heads low as if in pious humility.

Once there was also a field of buckwheat, and this field was exactly opposite to old willow-tree. The buckwheat did not bend like the other grain, but erected its head proudly and stiffly on the stem.

„I am as valuable as any other corn,“ said he, „and I am much handsomer; my flowers are as beautiful as the bloom of the apple blossom, and it is a pleasure to look at us. Do you know of anything prettier than we are, you old willow-tree?“

And the willow-tree nodded his head, as if he would say, „Indeed I do.“ But the buckwheat spread itself out with pride, and said, „Stupid tree. He is so old that grass grows out of his body.“

There arose a very terrible storm. All the field-flowers folded their leaves together, or bowed their little heads, while the storm passed over them, but the buckwheat stood erect in its pride.

„Bend your head as we do,“ said the flowers.

„I have no occasion to do so,“ replied the buckwheat.

„Bend your head as we do,“ cried the ears of corn; „the angel of the storm is coming. His wings spread from the sky above to the earth beneath. He will strike you down before you can cry for mercy.“

„But I will not bend my head,“ said the buckwheat.

„Close your flowers and bend your leaves,“ said the old willow-tree. „Do not look at the lightning when the cloud bursts; even men cannot do that. In a flash of lightning heaven opens, and we can look in; but the sight will strike even human beings blind. What then must happen to us, who only grow out of the earth, and are so inferior to them, if we venture to do so?“

„Inferior, indeed!“ said the buckwheat. „Now I intend to have a peep into heaven.“ Proudly and boldly he looked up, while the lightning flashed across the sky as if the whole world were in flames.

When the dreadful storm had passed, the flowers and the corn raised their drooping heads in the pure still air, refreshed by the rain, but the buckwheat lay like a weed in the field, burnt to blackness by the lightning.

The branches of the old willow-tree rustled in the wind, and large water-drops fell from his green leaves as if the old willow were weeping. Then the sparrows asked why he was weeping, when all around him seemed so cheerful. „See,“ they said, „how the sun shines, and the clouds float in the blue sky. Do you not smell the sweet perfume from flower and bush? Wherefore do you weep, old willow-tree?“

Then the willow told them of the haughty pride of the buckwheat, and of the punishment which followed in consequence. This is the story told me by the sparrows one evening when I begged them to relate some tale to me.

Learn languages. Double-tap on a word.Learn languages in context with Childstories.org and Deepl.com.

Learn languages. Double-tap on a word.Learn languages in context with Childstories.org and Deepl.com.Backgrounds

Interpretations

Adaptions

Summary

Linguistics

„The Buckwheat“ is a fairy tale written by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, who is best known for his other famous works such as „The Little Mermaid,“ „The Ugly Duckling,“ and „The Emperor’s New Clothes.“ Andersen’s fairy tales often contain moral lessons and are renowned for their timeless themes and appeal to both children and adults.

Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) was a Danish writer, poet, and playwright who gained international fame for his fairy tales. Born in Odense, Denmark, Andersen grew up in a poor family and struggled to establish himself as a writer. His first published works were poems and short stories, but it was his fairy tales that eventually brought him success and widespread acclaim.

Andersen’s fairy tales often feature elements of fantasy, magic, and folklore, and they frequently include moral lessons. Many of his stories have been adapted into various forms of media, including film, television, and theater productions. „The Buckwheat,“ although not as well-known as some of his other works, similarly contains a moral lesson about the importance of humility and the consequences of pride and arrogance.

The tale was first published in 1838 as part of Andersen’s third collection of fairy tales for children, „Fairy Tales Told for Children.“ The collection also includes other stories such as „The Wild Swans“ and „The Garden of Paradise.“

„The Buckwheat“ can be interpreted in several ways, offering valuable lessons and insights:

The importance of humility: The buckwheat’s arrogance and refusal to bow its head like the other plants ultimately lead to its destruction. This highlights the importance of humility and the need to recognize our own limitations.

Respecting nature’s power: The buckwheat’s defiance against the storm represents a lack of respect for the power of nature. By not heeding the warnings of the other plants and the old willow tree, the buckwheat faces the consequences of its own actions. This serves as a reminder of the importance of respecting and understanding nature’s power.

The consequences of pride: The story emphasizes the negative consequences of pride and arrogance. The buckwheat’s inflated sense of self-worth and refusal to listen to the advice of others ultimately leads to its demise. This demonstrates the importance of being open to the wisdom and experiences of others.

The value of community and shared wisdom: The old willow tree and other plants try to protect the buckwheat by sharing their knowledge and experiences. This suggests the importance of community, cooperation, and learning from one another in order to navigate through life’s challenges.

The fleeting nature of beauty: The buckwheat takes great pride in its appearance, believing itself to be more beautiful than other plants. However, its beauty is short-lived, as it is destroyed by the storm. This serves as a reminder that beauty can be temporary and that we should not place too much emphasis on external appearances.

„The Buckwheat“ by Hans Christian Andersen has inspired various adaptations and retellings over the years. Here are a few examples.

„The Buckwheat Boy,“ a picture book by Avelyn Davidson and illustrated by Gillian Johnson, retells the story of the buckwheat seed as a journey of self-discovery and transformation for a young boy.

„The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension,“ a science fiction film directed by W.D. Richter, features a character named Buckaroo Banzai who is a neurosurgeon, rock musician, and hero. The film’s title is a playful reference to the buckwheat seed’s journey through different dimensions.

„The Wheat and the Tares,“ a play by Karel Capek, is a satirical retelling of the buckwheat story, in which the wheat and the tares (weeds) engage in a battle of wits and strength for control of the field.

„The Buckwheat Pillow,“ a Japanese novel by Hideo Yokoyama, tells the story of a man who inherits a buckwheat pillow from his grandmother and embarks on a journey of self-discovery as he reflects on his family history and cultural heritage.

„The Buckwheat,“ a short film directed by Sean Branney, is a modern retelling of the story in which a man sets out to find the perfect buckwheat pancake and ends up on a journey of self-discovery and reflection.

These adaptations demonstrate the enduring appeal of „The Buckwheat“ and its themes of resilience, transformation, and community.

„The Buckwheat“ is a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen about the consequences of pride and arrogance. The story revolves around a field of buckwheat, an old willow tree, and the other plants and animals living nearby. The buckwheat, proud of its beautiful flowers, refuses to bow its head like other plants during a violent thunderstorm. The old willow tree, along with other flowers and ears of corn, tries to warn the buckwheat to humble itself, but the buckwheat refuses.

When the storm arrives, the angel of the storm sweeps through the fields. The other plants bow and close their flowers, but the buckwheat, in its arrogance, decides to look up into the heavens when the lightning flashes. As a result, the lightning strikes and blackens the buckwheat, leaving it burnt and destroyed.

After the storm, the old willow tree weeps, its branches rustling and water droplets falling from its leaves. When the sparrows ask why the tree is weeping, it tells them about the buckwheat’s pride and its subsequent punishment. The story serves as a cautionary tale, reminding us of the importance of humility and the dangers of arrogance.

Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale, „The Buckwheat,“ presents a moral narrative with a strong emphasis on humility and the consequences of pride. Through linguistic analysis, we can glean various stylistic and thematic elements that contribute to the tale’s enduring impact.

Narrative Style

Personification: Andersen employs personification extensively, giving human-like attributes to the buckwheat, willow-tree, corn, and even the storm. This technique creates an engaging and relatable narrative, enabling readers to view natural elements as characters in their own right. For example, the buckwheat is given prideful traits, while the willow-tree is depicted as wise and empathetic.

Dialogue: The use of dialogue between the buckwheat and other elements like the willow-tree, corn, and flowers serves to highlight contrasting perspectives. The dialogue is simple yet effective in conveying the moral lesson, with the buckwheat’s arrogance counterposed by the wise and cautionary advice of the willow-tree and the humility of the corn.

Imagery: Andersen’s narrative is vividly descriptive, painting a clear picture of the landscape and elements involved in the story. For instance, the description of the corn as „little golden canary-birds“ and the storm as an „angel“ with wings stretching from the sky to earth enrich the narrative with vibrant visual imagery and a touch of the supernatural.

Symbolism: The tale is heavily symbolic, with the buckwheat representing arrogance and the willow-tree symbolizing wisdom and experience. The storm and lightning symbolize natural justice or divine intervention, executing the consequences of pride.

Thematic Elements

Pride vs. Humility: The central theme centers on the dangers of pride and the virtue of humility. The buckwheat’s refusal to bend its head during the storm is a metaphor for its arrogance, contrasting with the humble corn that bows in reverence.

Consequences of Hubris: The narrative delivers a clear moral lesson on the consequences of hubris. The buckwheat’s desire to „peep into heaven“ and its subsequent destruction by lightning serve as a cautionary tale of the fallout from defying natural and divine order.

Wisdom of Experience: The old willow-tree’s advice is grounded in experience and symbolizes the wisdom that comes with age. Its initial response to the buckwheat’s arrogance is measured, and its subsequent sorrow underscores its understanding of the inevitable outcome.

Nature as Moral Authority: Andersen uses nature as a moral authority in the tale, where the natural elements respond justly to character traits. This positions nature as an omnipotent force that can punish or reward, reflecting the 19th-century romantic view of the natural world.

Conclusion

Andersen’s „The Buckwheat“ uses simple narrative techniques and rich symbolism to impart a timeless lesson about the perils of pride. Through personification, dialogue, vivid imagery, and allegory, Andersen crafts a fairy tale that resonates on moral, philosophical, and emotional levels, remaining relevant to readers across generations.

Information for scientific analysis

Fairy tale statistics | Value |

|---|---|

| Translations | DE, EN, DA, ES, IT, NL |

| Readability Index by Björnsson | 29.4 |

| Flesch-Reading-Ease Index | 80.8 |

| Flesch–Kincaid Grade-Level | 6.3 |

| Gunning Fog Index | 8.7 |

| Coleman–Liau Index | 8.3 |

| SMOG Index | 8.3 |

| Automated Readability Index | 6.5 |

| Character Count | 3.495 |

| Letter Count | 2.676 |

| Sentence Count | 38 |

| Word Count | 653 |

| Average Words per Sentence | 17,18 |

| Words with more than 6 letters | 80 |

| Percentage of long words | 12.3% |

| Number of Syllables | 838 |

| Average Syllables per Word | 1,28 |

| Words with three Syllables | 29 |

| Percentage Words with three Syllables | 4.4% |